Independent Left candidate Councillor John Lyons topped the poll in Artane-Whitehall 2024 for first preferences in the local government elections of 7 June 2024. This was a terrific result for our small party and above all is a recognition of the consistent, empathetic and determined work carried out by John for individuals and groups in the community he represents on Dublin City Council. The high vote might also be connected to the values and priorities of Independent Left and this deserves some reflection.

Before getting to that, however, what happened in the bigger picture? What do the results tell us about Irish politics in the snapshot provided by the election?

1. Fine Gael turned public concern onto the question of immigration.

It’s an old and, unfortunately, successful tactic by conservative and governing parties that to deflect from how they have facilitated the rich getting richer, they focus public anxiety on immigrants. In the run up to the election, Fine Gael, and their Fianna Fáil and Green partners in government, forced refugees into homelessness then arranged performances such as bulldozing tents to generate attention to the issue. This worked to put a spotlight on Sinn Féin’s response.

2. The Centre Held?

Ever since COVID restrictions gave fascists a focus to organise around, they’ve been growing in Ireland. By mobilising against refugee centres, they gained a following beyond a fringe. Encouraging people to be angry against immigrants plays right into the hands of these fascists. Fine Gael took a calculated risk on this: they chose to give fascism a boost rather than face the electorate on their record in government. After the election they breathed a sigh of relief and pundits everywhere said that the centre held. The reality, unfortunately, is that fascists did make significant gains. Not the gains that they themselves and their US funders hoped for, but about 5% of the electorate voted far-right in the European elections and in the local elections they got five seats, coming very close to a sixth in Artane-Whitehall.

3. Sinn Féin’s Troubles

Sinn Féin performed far worse than everyone predicted. In large part this was due to a weakness on the issue of immigration, although the tactical mistake of running too many candidates was costly too. The Sinn Féin line on immigration sounded evasive: better procedures are needed; the government is a shambles. On the doorstep, the left (politely) disagreed with anti-immigrant sentiment. Guided by resources like those of the Hope and Courage Collective we did our best to hear the underlying anger and turn it back towards the government and away from division. We can’t imagine Sinn Féin were as effective in these conversations, having implicitly conceded that immigration is a problem.

It also became evident that Sinn Féin were perceived by a surprising number of people as establishment-in-waiting rather than a radical party who could make a real difference.

4. The Social Democratic Left

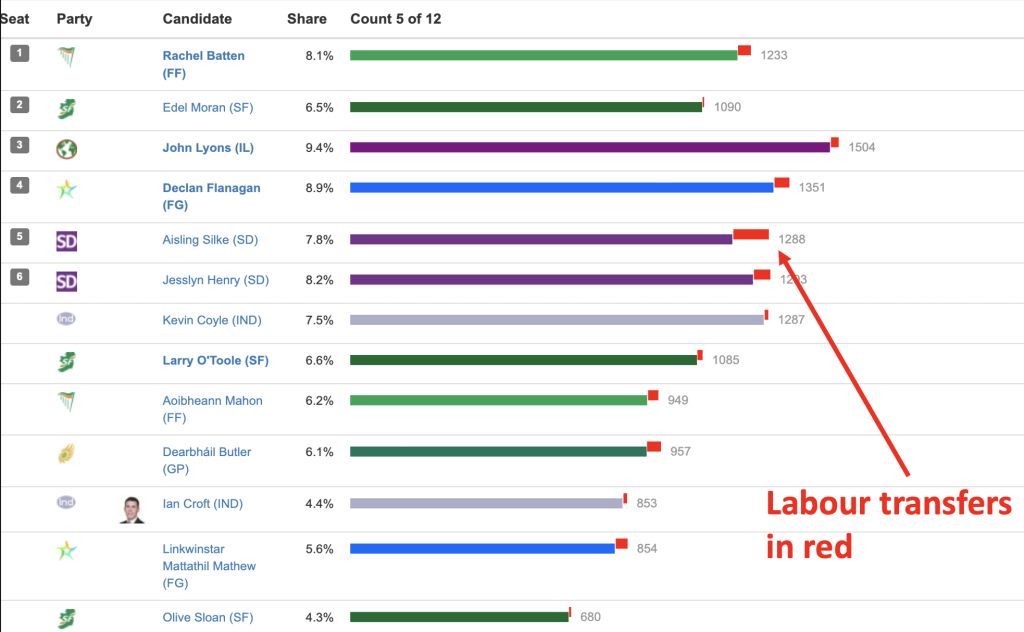

Labour didn’t lose ground in the local government elections, which must have been a relief given that they are being squeezed by the rise of the Social Democrats. And they gained a European seat in Dublin. The Social Democrats made modest progress. There is a difference between the two centre left parties, as evidenced by where their transfers went. While the SocDems showed a slight preference for Labour, they also transferred well to Greens and People Before Profit. Labour voters, as could be seen in Artane-Whitehall, much preferred a government party to Independent Left, transferring more than twice as heavily to Fine Gael and Fianna Fail than to John Lyons. This might have implications for whether the Labour leadership prefer to work with Fianna Fail and Fine Gael than a left alliance, as evidenced by the negotiations for a ruling group in Dublin City Council, where Labour have refused to cooperate with a left initiative.

The formation of a leading group on Dublin City Council after the 2024 election is instructive. Sinn Féin (9 seats) and the Social Democrats (10 seats) proposed to Labour (4) and the Green Party (8) as well as PBP (2), Independent Left and others on the left that a group be formed with a commitment to the inclusivity and using what resources the council has on behalf of those who need it most, including the idea of the re-municipalisation of waste.

Independent Left Councilor John Lyons was willing to support this initiative – with the caveat that this did not commit us to voting for every resolution, mayoral candidate or budget proposed by alliance members – but Labour refused to support a left project, prompting John Lyons to say:

To see Green and Labour councillors moving toward an agreement with Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael at the expense of a genuine progressive alliance which has the potential to make such a positive impact on the lives of Dubliners is, to my mind, unforgivable.

They’ve truly lost their way.

5. People Before Profit / Socialist Party / Right2Change

Explicitly socialist parties and individuals did quite well. People Before Profit went from 6 to 10 seats, albeit two of those were at the expense of the Socialist Party, who ended up with 3 councillors. Pat Dunne for Right2Change held his seat, as did independent Cieran Perry. Pat English in Clonmel held his seat, as did Ted Tynan in Cork, although unfortunately Lorna Bogue lost hers in Cork. Dean Mulligan took a seat in Swords on the first count and Declan Bree kept his seat in Sligo. Other independents on the left include Jimmy Brogan (Donegal); John Dwyer (New Ross); and Mícheal Choilm Mac Giolla Easbuig (Glenties). Apologies to anyone we missed.

So by way of discussion, are there any lessons from the 2024 election for those wanting radical change?

Quick out of the blocks are those saying the main lesson is that the left should unite in forming an electoral pact for a left government in Ireland.

Independent Left are very willing to support unity on the left, including election pacts. The idea of forming a left government with Sinn Féin, though, needs a reality check. The hundred-year history of left governments, without exception, is a history of failure. The reason for this is structural, rather than any lack of principle among the elected socialists. Short version: you can no more stand in the way of capitalism by passing legislation in the Dáil than you can stop a tsunami by digging a small trench.

Should Independent Left have a TD following a general election, we would support all positive legislation proposed by a left government, but not join it. We would want to keep our freedom to criticise and to speak and organise against the government when necessary.

Imagination not pragmatic politics is at the heart of fundamental transformations in human history. Martin Luther King’s most powerful speech included a refrain that he had a dream: a dream of black and white people living together as equals. The equivalent to that speech is needed in the world today with regard to imagining an alternative to capitalism.

Independent Left are dreamers in this sense. Of course we help the communities we are part of obtain the investment they deserve – new sports grounds, housing, meeting centres – and of course we’d welcome a left government, especially one that set about building affordable housing. But at the same time, we are not going to give up on our dreams for the sake of supporting a government that must inevitably fall, perhaps demoralising their supporters as severely as did Syriza in Greece in 2019.

The type of changes necessary to get humanity out of the mess we are in are really deep. They include taking the wealth from the billionaires and redistributing it and they also include a fundamental, bottom to top, transformation in the way that we live and work, not least in creating a world where disability is no obstacle to independent living and the phasing out of animal farming. No Sinn Féin-led government is going to have such radical ambition.

Which brings us back to the question of whether Independent Left are doing something right in both having such radical ambition and managing to develop community support around John Lyons. Well, perhaps, to some extent. You can see our main election leaflet if you scroll down here. In a lot of ways, it is similar to other socialist messages: we want to address the unfair distribution of investment by Dublin City Council and we strive to get more affordable housing built, along with the necessary schools, GP services and traffic systems to integrate these. Other priorities are disability rights and active travel around Dublin.

Where Councillor John Lyons and Independent Left are currently somewhat different to most Irish socialists is in our opposition to all imperialism, both Israel’s US-backed genocide against Palestinians and Putin’s invasion of Ukraine. The other notable difference is our advocacy of animal rights. These policies seem to have done no harm electorally and the latter might well have been attractive to those increasingly concerned about the horrendous treatment of animals here.

Finally, there’s a difference in approach too, which might be unique. Independent Left members include anarchists and that brings an emphasis on listening to community activists and campaigners on specific issues and learning from them. John himself has been a steady and consistent participant in many community campaigns, often ones that have been ongoing for years. If you are a socialist or Sinn Féin activist who appears for elections or to advertise immediate, urgent demonstrations but then disappears in between, you won’t create lasting relationships with those who are serious about addressing the needs of the community.

Maybe it’s our small size, and there will be challenges if we were to grow significantly, but nearly all our decisions are made by consensus. WhatsApp chat is a useful day-to-day supplement to more formal meetings and allows everyone to know what issues have come up for each other.

The Irish left have a lot of work to do, not least in checking the progress of the far right. Independent Left will play our part and cooperate with all others both electorally, in constructive efforts to get the most resources from Dublin City Council for those who need it most, and in joint campaigns. We’ll also continue to develop our approach to combining a commitment to practical and immediate work with our dreams of a better world.