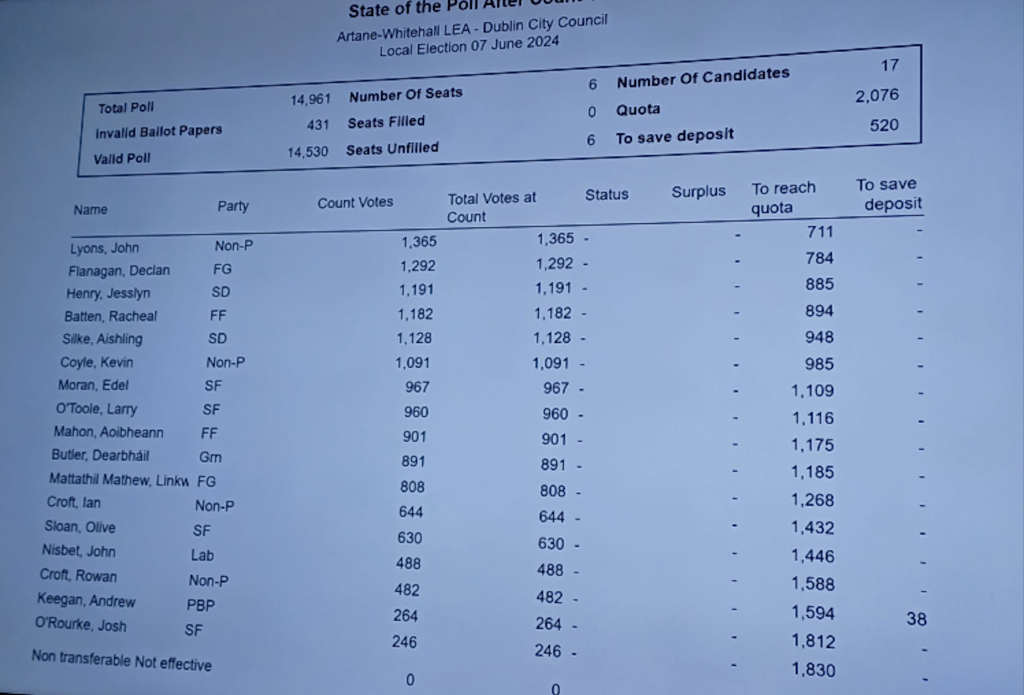

Artane Whitehall 2024 Local Election Results, Tallies, Counts

The Artane Whitehall 2024 constituency for the local government election to Dublin City Council consists of Artane, Beaumont, Belcamp, Clonshaugh, Coolock, Darndale, Kilmore West, Santry, and Whitehall. The local government elections in Ireland took place on 7 June 2024.

There were six seats available in Artane – Whitehall. Fine Gael ran two candidates; Fianna Fáil two; the Greens one; Labour one; the Social Democrats two; Sinn Féin four and of course Councillor John Lyons ran for Independent Left.

Councillor John Lyons retained his seat, after topping the poll on the first count.

Here are the results of the count.

The Official First Count for Artane – Whitehall Local Government Council Election 2024

A fantastic result for Councillor John Lyons who topped the poll in Artane Whitehall.

Councillor John Lyons topped the poll and retained his seat. This was very welcome news of course but the growth of support for the far right in the constituency means there is a lot of work to be done for the community to show that unity not division is the way forward.

Councillor John Lyon’s leaflet for the local government election 2024 said:

An Honour to Serve Artane Whitehall in Local Government

It has been an honour to serve as your Dublin City councillor since I was first elected in 2014 and am asking for your No. 1 vote on Friday 7 June as I run for re-election.

Councillor John Lyons

As a councillor, I’ve helped our community challenge the unfair way that Dublin City Council operates. Decisions are made which put plenty of money into the bank accounts of developers, but when it comes to funding local services and amenities, it’s always an uphill struggle. Recent analysis of DCC’s capital expenditure clearly shows that this area of the city has received the least amount of investment of all areas. This is completely unacceptable.

The focus of my advocacy for the people of Artane, Beaumont, Belcamp, Clonshaugh, Coolock, Darndale, Kilmore West, Santry, and Whitehall is in the following areas.

Housing & Planning

I want high quality, energy-efficient social and affordable housing to be delivered in such numbers that we finally end the housing and homelessness crises. The main reason that Ireland has a massive housing crisis is that from 1990 successive governments stopped investing in state-built homes. The government parties are highly networked among developers and landlords (many FF and FG TDs and councillors are landlords), the very people who benefit from the housing and homelessness crisis.

We need:

- A full programme of directly built, public and affordable housing delivered by local and national government.

- To stop evictions into homelessness.

- To introduce rent controls and reductions: ensure that nobody is paying more than 30% of their income on rent.

- Stop selling off public land that could be used to address the housing crisis

We need a more democratic, community-centred planning system which treats planning applications in a holistic manner. The new residential developments we so badly require to address the housing crisis must be delivered along with the community, educational and health facilities required for new and existing communities to integrate properly together.

Community Investment

We deserve more sports facilities, community centres, well-maintained areas and playgrounds. Such facilities help foster a sense of community and add life and vibrancy to our areas. Without them, anti-social behaviour grows. The volunteer work that people do in the community is inspiring and it should be backed by investment from DCC.

My successful motion to DCC for a publicly-owned all-weather football facility in Artane-Whitehall is finally being delivered on, with the site currently being selected. But we need a lot more, just to catch up with the levels of investment other areas have obtained from DCC, such as a new Community Centre for Coolock where many groups like the Priorswood & District Men’s Shed can meet.

Disability Rights

We all know people with extra needs and it’s shocking how hard it is to get the support that people with disabilities are entitled to and deserve. I want people with disabilities to be able to live independently and with the same access to jobs, education, and amenities as everyone else. They rarely say it openly, but from the point of view of the government, people with disabilities are an unaffordable burden and their funding priorities reflect this. Even when we do have rights in theory, such as to reasonable accommodation in the workplace, it’s a non-stop and exhausting battle to obtain them. I support the goals of Disability Power Ireland, the Independent Living Movement Ireland, Neuropride Ireland and all those campaigning for disability rights.

Active Travel

I want to help create a Dublin that is easy, safe and pleasant to travel around. I will continue to support Dublin City Council’s Active Travel Network which aims to enhance the quality of life of Dubliners by connecting all people through the delivery of an integrated 310 km walk-wheel-cycle network.

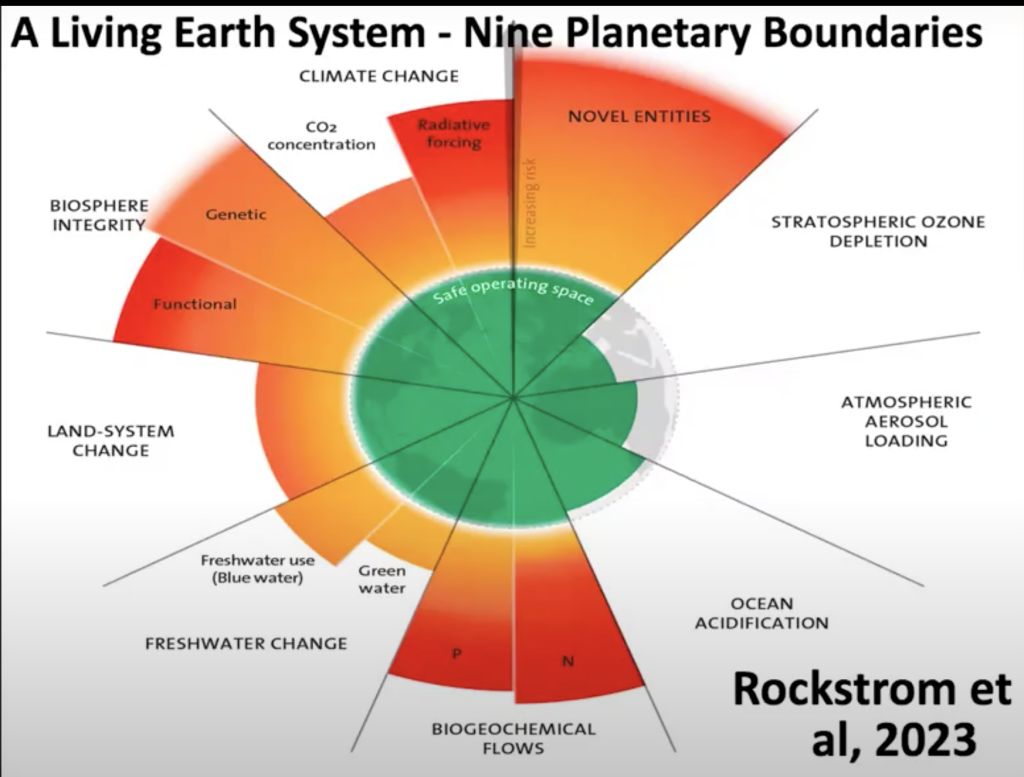

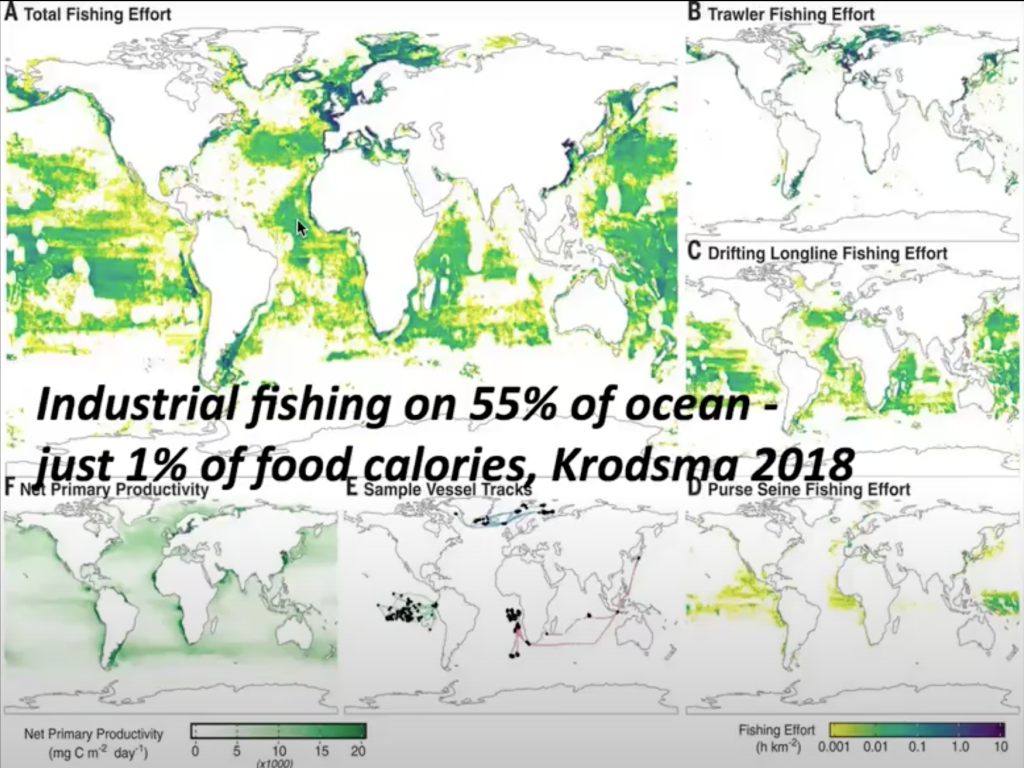

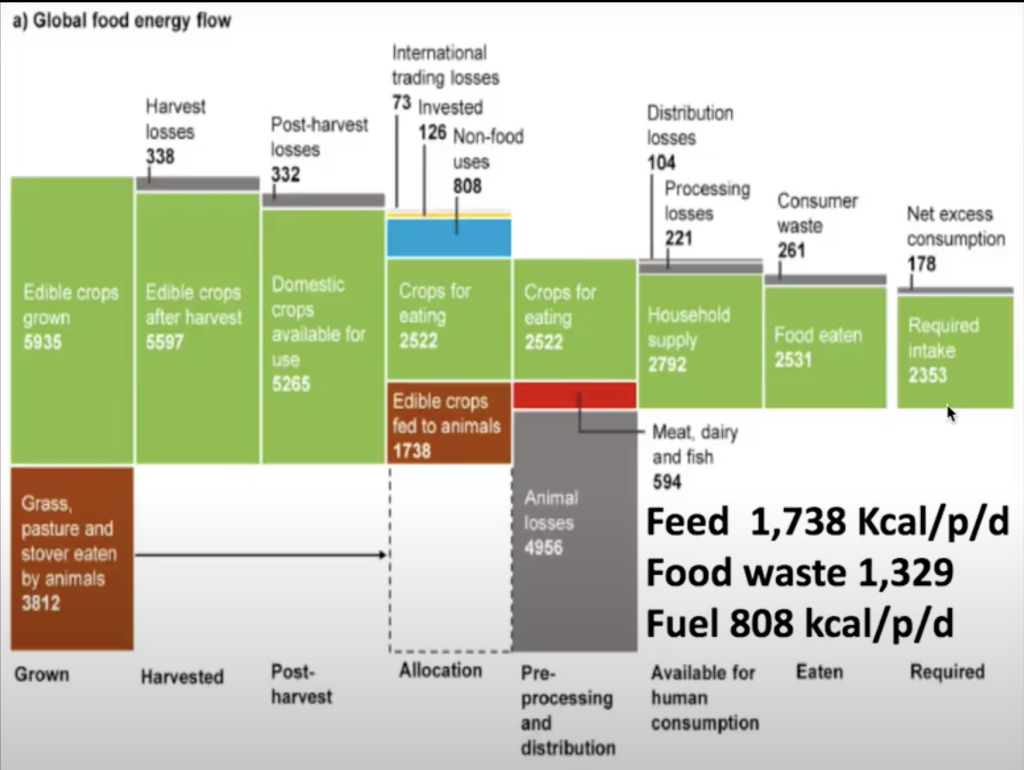

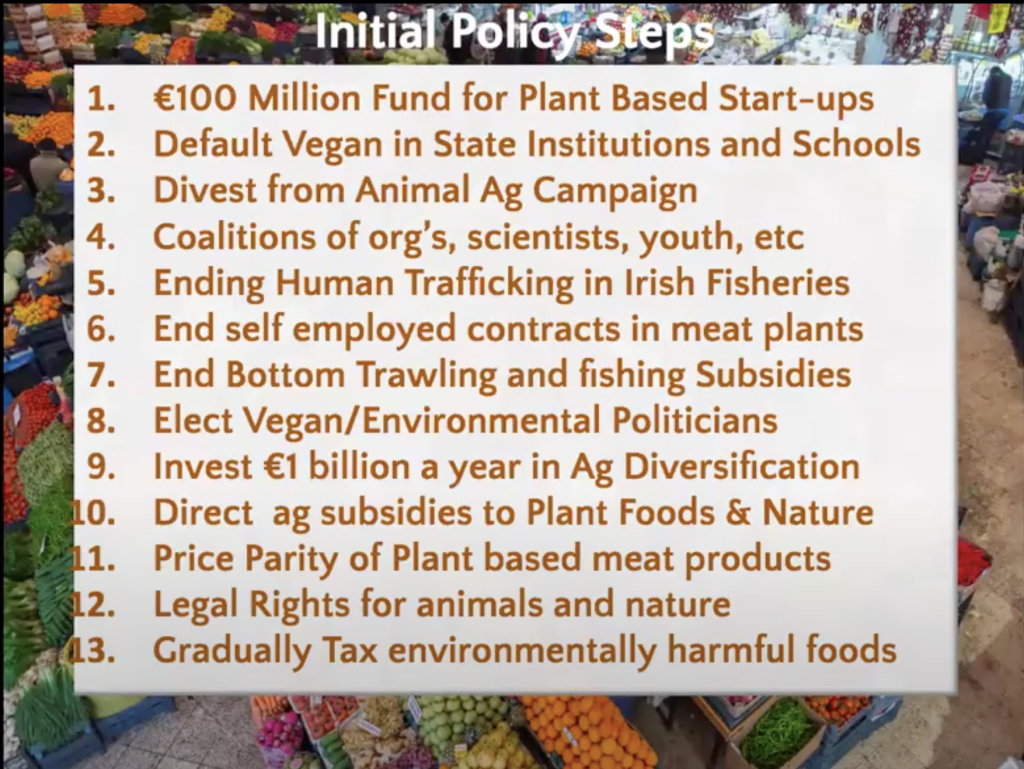

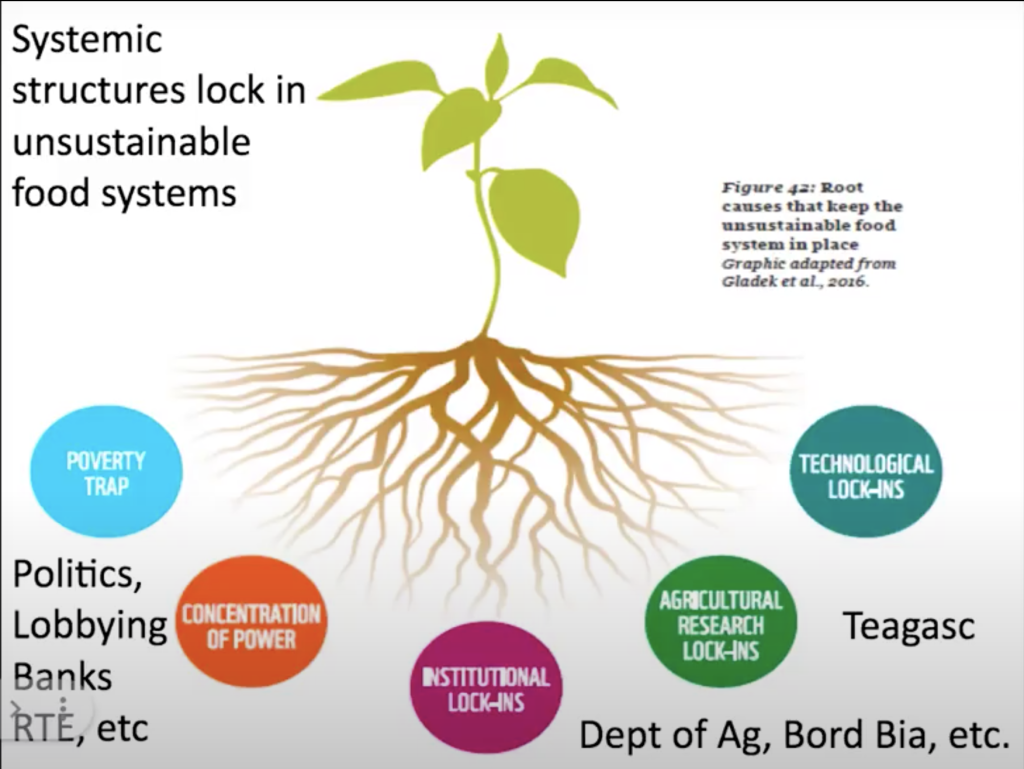

Climate Change and Animal Rights

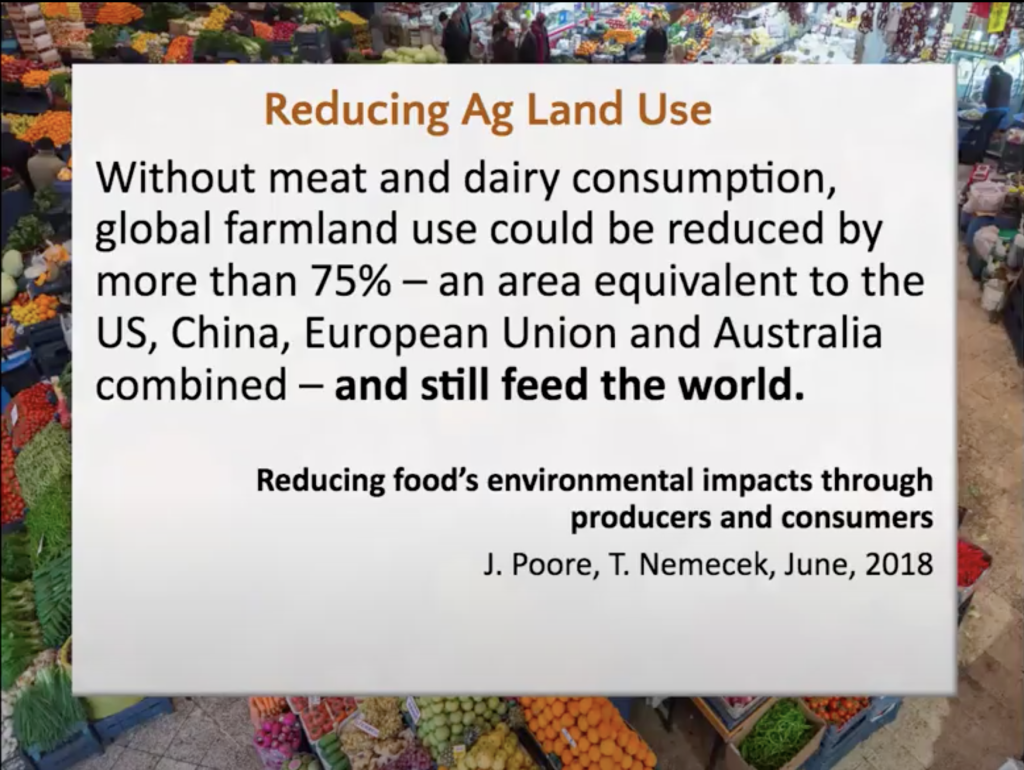

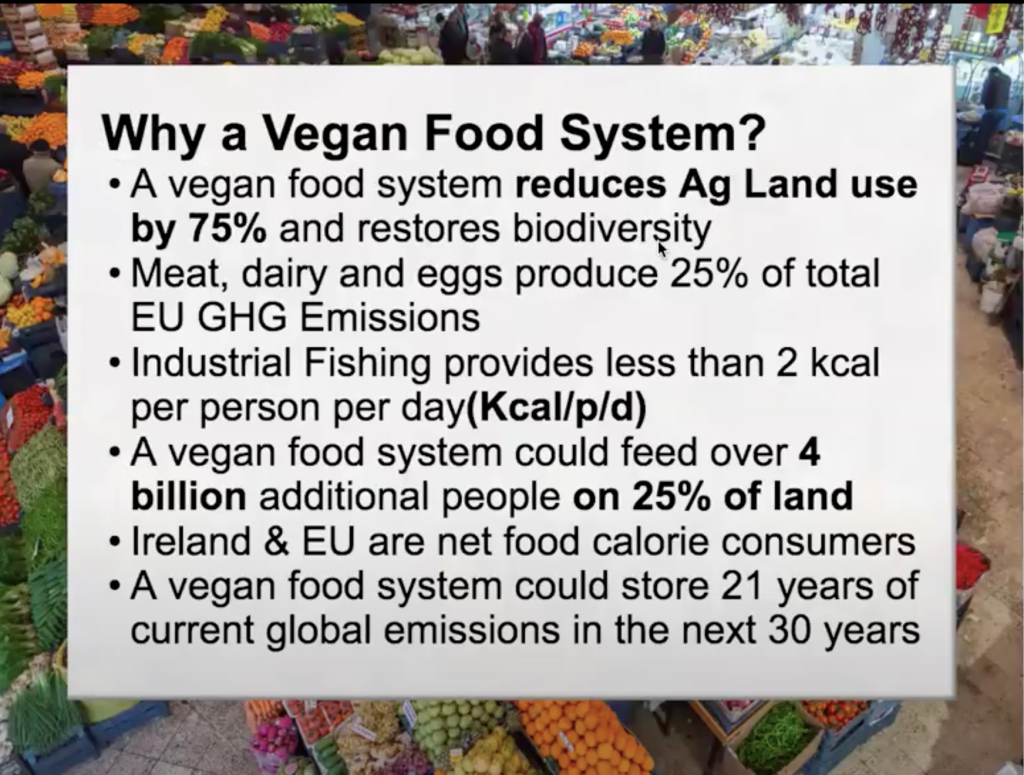

Instead of transitioning towards a harmonious relationship between humans and the environment, the planet continues to heat and wildlife continues to be driven to extinction. We could—and should—implement more green policies locally, but real fundamental change is needed across the world, including a reappraisal of our relationship to animals. I want to see an end to the mistreatment of animals and now believe that Ireland’s food system needs to transition to one that is ethical, sustainable and plant-based.

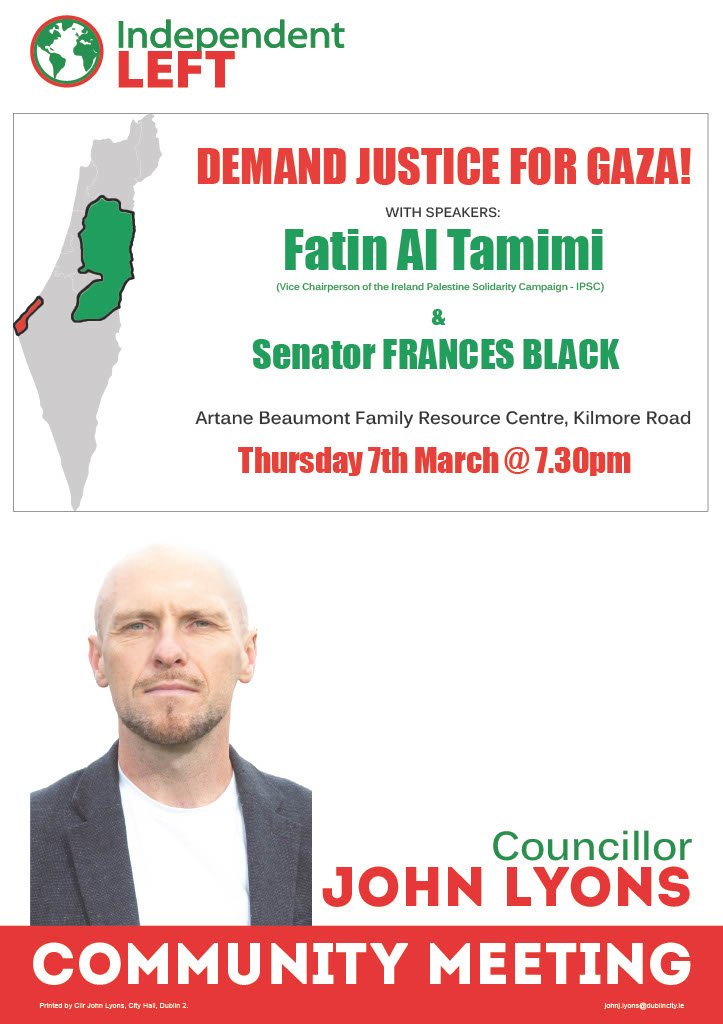

Opposition to War

For decades it seemed as though the horrors of events like the Second World War were behind us. But the word’s imperial powers are once more resorting to state violence in a race to control the world’s resources. The unbearable suffering of Palestine has its origins in the creation of Israel as a watchdog for US interests in the Middle East. Putin’s invasion of Ukraine is another act of imperialism and I was a founding member of Irish Left with Ukraine in order to offer aid and solidarity to the people of Ukraine.

We live in a world which in the last year in particular has become a darker place, with the growing impact of climate change, war in Ukraine, and the genocide in Gaza. This affects us all but especially the young, whose levels of depression and anxiety are soaring.

As a councillor I strive not only to give voice to our local community, but also to use my role as much as I can to make the world a better place.

Councillor John Lyons

Artane Whitehall 2024 Election: Unity Over Division

Unity Over Division

In recent months there have been attempts to divide our communities with the dehumanisation of people seeking safety in Ireland. It suits the government to focus on this issue and not their own record on housing, healthcare, and education. Then there is the Far-Right, who want people to punch down, to target anger and hate at the people seeking international protection. I’ve never seen any of them offer the slightest support to the community when we are standing together in campaigns on housing and community investment.

I believe every human being has the right to try to make a better life for themselves, as we did and as our young people still are doing when they are forced to emigrate for lack of affordable homes. Our communities are warm and welcoming places filled with great people and wonderful neighbours. We are better and stronger when we are united.

MY PLEDGE

Never to vote for the sale of public land for private profit

To vote against and fight any further reduction in council responsibilities

To fight against racism and discrimination in all its forms and welcome people seeking refuge in Dublin

Never do any deals with Fine Gael or Fianna Fail

Never participate in any council junkets

Vote Number 1 Councillor John Lyons for Artane Whitehall 2024 Dublin Local Government Election

Running for Dublin City council for the people of Artane, Beaumont, Belcamp, Clonshaugh, Coolock, Darndale, Kilmore West, Santry and Whitehall.

To support John, contact him directly johnj.lyons@dublincity.ie; instagram; Facebook; X; or phone 087-7729292.

You can help fund John’s election campaign.

To join Independent Left’s mailing list, scroll down to the bottom of the page here.

The Artane Whitehall local elections interview with John Lyons on Northside Today: